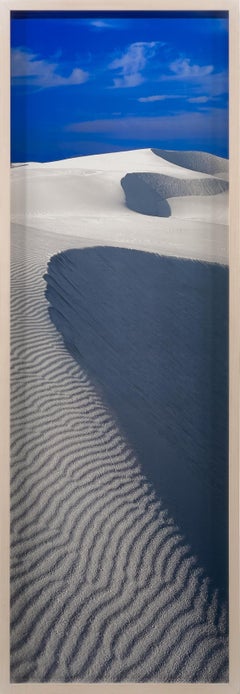

My own private Travel Diary - Bishop, CA - Autumn - 2001,

20x29cm,

Edition of 10, plus 2 Artist Proofs.

Archival C-Print, based on a Polaroid Slide.

Signature label and Certificate.

Not mounted.

LIFE’S A DREAM

(The Personal World of Stefanie Schneider) by Mark Gisbourne

Projection is a form of apparition that is characteristic of our human nature, for what we imagine almost invariably transcends the reality of what we live. And, an apparition, as the word suggests, is quite literally ‘an appearing’, for what we appear to imagine is largely shaped by the imagination of its appearance. If this sounds tautological then so be it. But the work of Stefanie Schneider is almost invariably about chance and apparition. And, it is through the means of photography, the most apparitional of image-based media, that her pictorial narratives or photo-novels are generated. Indeed, traditional photography (as distinct from new digital technology) is literally an ‘awaiting’ for an appearance to take place, in line with the imagined image as executed in the camera and later developed in the dark room. The fact that Schneider uses out-of-date Polaroid film stock to take her pictures only intensifies the sense of their apparitional contents when they are realised. The stability comes only at such time when the images are re-shot and developed in the studio, and thereby fixed or arrested temporarily in space and time.

The unpredictable and at times unstable film she adopts for her works also creates a sense of chance within the outcome that can be imagined or potentially envisaged by the artist Schneider. But this chance manifestation is a loosely controlled, or, better called existential sense of chance, which becomes pre-disposed by the immediate circumstances of her life and the project she is undertaking at the time. Hence the choices she makes are largely open-ended choices, driven by a personal nature and disposition allowing for a second appearing of things whose eventual outcome remains undefined. And, it is the alliance of the chance-directed material apparition of Polaroid film, in turn explicitly allied to the experiences of her personal life circumstances, that provokes the potential to create Stefanie Schneider’s open-ended narratives. Therefore they are stories based on a degenerate set of conditions that are both material and human, with an inherent pessimism and a feeling for the sense of sublime ridicule being seemingly exposed. This in turn echoes and doubles the meaning of the verb ‘to expose’. To expose being embedded in the technical photographic process, just as much as it is in the narrative contents of Schneider’s photo-novel exposés. The former being the unstable point of departure, and the latter being the uncertain ends or meanings that are generated through the photographs doubled exposure.

The large number of speculative theories of apparition, literally read as that which appears, and/or creative visions in filmmaking and photography are self-evident, and need not detain us here. But from the earliest inception of photography artists have been concerned with manipulated and/or chance effects, be they directed towards deceiving the viewer, or the alchemical investigations pursued by someone like Sigmar Polke. None of these are the real concern of the artist-photographer Stefanie Schneider, however, but rather she is more interested with what the chance-directed appearances in her photographs portend. For Schneider’s works are concerned with the opaque and porous contents of human relations and events, the material means are largely the mechanism to achieving and exposing the ‘ridiculous sublime’ that has come increasingly to dominate the contemporary affect(s) of our world. The uncertain conditions of today’s struggles as people attempt to relate to each other - and to themselves - are made manifest throughout her work. And, that she does this against the backdrop of the so-called ‘American Dream’, of a purportedly advanced culture that is Modern America, makes them all the more incisive and critical as acts of photographic exposure.

From her earliest works of the late nineties one might be inclined to see her photographs as if they were a concerted attempt at an investigative or analytic serialisation, or, better still, a psychoanalytic dissection of the different and particular genres of American subculture. But this is to miss the point for the series though they have dates and subsequent publications remain in a certain sense unfinished. Schneider’s work has little or nothing to do with reportage as such, but with recording human culture in a state of fragmentation and slippage. And, if a photographer like Diane Arbus dealt specifically with the anomalous and peculiar that made up American suburban life, the work of Schneider touches upon the alienation of the commonplace. That is to say how the banal stereotypes of Western Americana have been emptied out, and claims as to any inherent meaning they formerly possessed has become strangely displaced. Her photographs constantly fathom the familiar, often closely connected to traditional American film genre, and make it completely unfamiliar. Of course Freud would have called this simply the unheimlich or uncanny. But here again Schneider almost never plays the role of the psychologist, or, for that matter, seeks to impart any specific meanings to the photographic contents of her images. The works possess an edited behavioural narrative (she has made choices), but there is never a sense of there being a clearly defined story. Indeed, the uncertainty of my reading here presented, acts as a caveat to the very condition that Schneider’s photographs provoke.

Invariably the settings of her pictorial narratives are the South West of the United States, most often the desert and its periphery in Southern California. The desert is a not easily identifiable space, with the suburban boundaries where habitation meets the desert even more so. There are certain sub-themes common to Schneider’s work, not least that of journeying, on the road, a feeling of wandering and itinerancy, or simply aimlessness. Alongside this subsidiary structural characters continually appear, the gas station, the automobile, the motel, the highway, the revolver, logos and signage, the wasteland, the isolated train track and the trailer. If these form a loosely defined structure into which human characters and events are cast, then Schneider always remains the fulcrum and mechanism of their exposure. Sometimes using actresses, friends, her sister, colleagues or lovers, Schneider stands by to watch the chance events as they unfold. And, this is even the case when she is a participant in front of camera of her photo-novels. It is the ability to wait and throw things open to chance and to unpredictable circumstances, that marks the development of her work over the last eight years. It is the means by which random occurrences take on such a telling sense of pregnancy in her work.

However, in terms of analogy the closest proximity to Schneider’s photographic work is that of film. For many of her titles derive directly from film, in photographic series like OK Corral (1999), Vegas (1999), Westworld (1999), Memorial Day (2001), Primary Colours (2001), Suburbia (2004), The Last Picture Show (2005), and in other examples. Her works also include particular images that are titled Zabriskie Point, a photograph of her sister in an orange wig. Indeed the tentative title for the present publication Stranger Than Paradise is taken from Jim Jarmusch’s film of the same title in 1984. Yet it would be dangerous to take this comparison too far, since her series 29 Palms (1999) presages the later title of a film that appeared only in 2002. What I am trying to say here is that film forms the nexus of American culture, and it is not so much that Schneider’s photographs make specific references to these films (though in some instances they do), but that in referencing them she accesses the same American culture that is being emptied out and scrutinised by her photo-novels. In short her pictorial narratives might be said to strip films of the stereotypical Hollywood tropes that many of them possess. Indeed, the films that have most inspired her are those that similarly deconstruct the same sentimental and increasingly tawdry ‘American Dream’ peddled by Hollywood. These include films like David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986), Wild at Heart (1990) The Lost Highway (1997), John Dahl’s The Last Seduction (1994) or films like Ridley Scott’s Thelma and Louise with all its girl-power Bonny and Clyde-type clichés. But they serve no more than as a backdrop, a type of generic tableau from which Schneider might take human and abstracted elements, for as commercial films they are not the product of mere chance and random occurrence.

Notwithstanding this observation, it is also clear that the gender deconstructions that the characters in these films so often portray, namely the active role of women possessed of a free and autonomous sexuality (even victim turned vamp), frequently find resonances within the behavioural events taking place in Schneider’s photographs and DVD sequences; the same sense of sexual autonomy that Stefanie Schneider possesses and is personally committed to.

In the series 29 Palms (first begun in 1999) the two women characters Radha and Max act out a scenario that is both infantile and adolescent. Wearing brightly coloured fake wigs of yellow and orange, a parody of the blonde and the redhead, they are seemingly trailer park white trash possessing a sentimental and kitsch taste in clothes totally inappropriate to the locality. The fact that Schneider makes no judgment about this is an interesting adjunct. Indeed, the photographic projection of the images is such that the girls incline themselves to believe that they are both beautiful and desirous. However, unlike the predatory role of women in say Richard Prince’s photographs, which are simply a projection of a male fantasy onto women, Radha and Max are self-contained in their vacuous if empty trailer and motel world of the swimming pool, nail polish, and childish water pistols. Within the photographic sequence Schneider includes herself, and acts as a punctum of disruption. Why is she standing in front of an Officers’ Wives Club? Why is Schneider not similarly attired? Is there a proximity to an army camp, are these would-be Lolita(s) Rahda and Max wives or American marine groupies, and where is the centre and focus of their identity? It is the ambiguity of personal involvement that is set up by Schneider which deliberately makes problematic any clear sense of narrative construction. The strangely virulent colours of the bleached-out girls stand in marked contrast to Schneider’s own anodyne sense of self-image. Is she identifying with the contents or directing the scenario? With this series, perhaps, more than any other, Schneider creates a feeling of a world that has some degree of symbolic order. For example the girls stand or squat by a dirt road, posing the question as to their sexual and personal status. Following the 29 Palms series, Schneider will trust herself increasingly by diminishing the sense of a staged environment. The events to come will tell you both everything and nothing, reveal and obfuscate, point towards and simultaneously away from any clearly definable meaning.

If for example we compare 29 Palms to say Hitchhiker (2005), and where the sexual contents are made overtly explicit, we do not find the same sense of simulated identity. It is the itinerant coming together of two characters Daisy and Austen, who meet on the road and subsequently share a trailer together. Presented in a sequential DVD and still format, we become party to a would-be relationship of sorts. No information is given as to the background or social origins, or even any reasons as to why these two women should be attracted to each other. Is it acted out? Are they real life experiences? They are women who are sexually free in expressing themselves. But while the initial engagement with the subject is orchestrated by Schneider, and the edited outcome determined by the artist, beyond that we have little information with which to construct a story. The events are commonplace, edgy and uncertain, but the viewer is left to decide as to what they might mean as a narrative. The disaggregated emotions of the work are made evident, the game or role playing, the transitory fantasies palpable, and yet at the same time everything is insubstantial and might fall apart at any moment. The characters relate but they do not present a relationship in any meaningful sense. Or, if they do, it is one driven the coincidental juxtaposition of random emotions. Should there be an intended syntax it is one that has been stripped of the power to grammatically structure what is being experienced. And, this seems to be the central point of the work, the emptying out not only of a particular American way of life, but the suggestion that the grounds upon which it was once predicated are no longer possible. The photo-novel Hitchhiker is porous and the culture of the seventies which it might be said to homage is no longer sustainable. Not without coincidence, perhaps, the decade that was the last ubiquitous age of Polaroid film.

In the numerous photographic series, some twenty or so, that occur between 29 Palms and Hitchhiker, Schneider has immersed herself and scrutinised many aspects of suburban, peripheral, and scrubland America. Her characters, including herself, are never at the centre of cultural affairs. Such eccentricities as they might possess are all derived from what could be called their adjacent status to the dominant culture of America. In fact her works are often sated with references to the sentimental sub-strata that underpin so much of American daily life. It is the same whether it is flower gardens and household accoutrements of her photo-series Suburbia (2004), or the transitional and environmental conditions depicted in The Last Picture Show (2005). The artist’s use of sentimental song titles, often adapted to accompany individual images within a series by Schneider, show her awareness of America’s close relationship between popular film and music. For example the song ‘Leaving on a Jet Plane’, becomes Leaving in a Jet Plane as part of The Last Picture Show series, while the literalism of the plane in the sky is shown in one element of this diptych, but juxtaposed to a blonde-wigged figure first seen in 29 Palms. This indicates that every potential narrative element is open to continual reallocation in what amounts to a story without end. And, the interchangeable nature of the images, like a dream, is the state of both a pictorial and affective flux that is the underlying theme pervading Schneider’s photo-narratives. For dream is a site of yearning or longing, either to be with or without, a human pursuit of a restless but uncertain alternative to our daily reality.

The scenarios that Schneider sets up nonetheless have to be initiated by the artist. And, this might be best understood by looking at her three recent DVD sequenced photo-novels, Reneé’s Dream and Sidewinder (2005). We have already considered the other called Hitchhiker. In the case of Sidewinder the scenario was created by internet where she met J.D. Rudometkin, an ex-theologian, who agreed to her idea to live with her for five weeks in the scrubland dessert environment of Southern California. The dynamics and unfolding of their relationship, both sexually and emotionally, became the primary subject matter of this series of photographs. The relative isolation and their close proximity, the interactive tensions, conflicts and submissions, are thus recorded to reveal the day-to-day evolution of their relationship. That a time limit was set on this relation-based experiment was not the least important aspect of the project. The text and music accompanying the DVD were written by the American Rudometkin, who speaks poetically of “Torn Stevie. Scars from the weapon to her toes an accidental act of God her father said. On Vaness at California.” The mix of hip reverie and fantasy-based language of his text, echoes the chaotic unfolding of their daily life in this period, and is evident in the almost sun-bleached Polaroid images like Whisky Dance, where the two abandon themselves to the frenetic circumstances of the moment. Thus Sidewinder, a euphemism for both a missile and a rattlesnake, hints at the libidinal and emotional dangers that were risked by Schneider and Rudometkin. Perhaps, more than any other of her photo-novels it was the most spontaneous and immediate, since Schneider’s direct participation mitigated against and narrowed down the space between her life and the art work. The explicit and open character of their relationship at this time (though they have remained friends), opens up the question as the biographical role Schneider plays in all her work. She both makes and directs the work while simultaneously dwelling within the artistic processes as they unfold. Hence she is both author and character, conceiving the frame within which things will take place, and yet subject to the same unpredictable outcomes that emerge in the process.

In Reneé’s Dream, issues of role reversal take place as the cowgirl on her horse undermines the male stereotype of Richard Prince’s ‘Marlboro Country’. This photo-work along with several others by Schneider, continue to undermine the focus of the male gaze, for her women are increasingly autonomous and subversive. They challenge the male role of sexual predator, often taking the lead and undermining masculine role play, trading on male fears that their desires can be so easily attained. That she does this by working through archetypal male conventions of American culture, is not the least of the accomplishments in her work. What we are confronted with frequently is of an idyll turned sour, the filmic clichés that Hollywood and American television dramas have promoted for fifty years. The citing of this in the Romantic West, where so many of the male clichés were generated, only adds to the diminishing sense of substance once attributed to these iconic American fabrications. And, that she is able to do this through photographic images rather than film, undercuts the dominance espoused by time-based film. Film feigns to be seamless though we know it is not. Film operates with a story board and setting in which scenes are elaborately arranged and pre-planned. Schneider has thus been able to generate a genre of fragmentary events, the assemblage of a story without a storyboard. But these post-narratological stories require another component, and that component is the viewer who must bring their own interpretation as to what is taking place. If this can be considered the upside of her work, the downside is that she never positions herself by giving a personal opinion as to the events that are taking place in her photographs. But, perhaps, this is nothing more than her use of the operation of chance dictates.

I began this essay by speaking about the apparitional contents of Stefanie Schneider’s pictorial narratives, and meant at that time the literal and chance-directed ‘appearing’ qualities of her photographs. Perhaps, at this moment we should also think of the metaphoric contents of the word apparition. There is certainly a spectre-like quality also, a ghostly uncertainty about many of the human experiences found in her subject matter. Is it that the subculture of the American Dream, or the way of life Schneider has chosen to record, has in turn become also the phantom of it former self? Are these empty and fragmented scenarios a mirror of what has become of contemporary America? There is certainly some affection for their contents on the part of the artist, but it is somehow tainted with pessimism and the impossibility of sustainable human relations, with the dissolute and commercial distractions of America today. Whether this is the way it is, or, at least, the way it is perceived by Schneider is hard to assess. There is a bleak lassitude about so many of her characters. But then again the artist has so inured herself into this context over a long protracted period that the boundaries between the events and happenings photographed, and the personal life of Stefanie Schneider, have become similarly opaque. Is it the diagnosis of a condition, or just a recording of a phenomenon? Only the viewer can decide this question. For the status of Schneider’s certain sense of uncertainty is, perhaps, the only truth we may ever know.

1 Kerry Brougher (ed.), Art and Film Since 1945: Hall of Mirrors, ex. cat., The Museum of Contemporary Art (New York, 1996)

2 Im Reich der Phantome: Fotographie des Unsichtbaren, ex. cat., Städtisches Museum Abteiberg Mönchengladbach/Kunsthalle Krems/FotomuseumWinterthur, (Ostfildern-Ruit, 1997)

3 Photoworks: When Pictures Vanish – Sigmar Polke, Museum of Contemporary Art (Zürich-Berlin-New York, 1995)

4 Slavoj Žižek, The Art of the Ridiculous Sublime: On David Lynch’s Lost Highway, Walter Chapin

Simpson Center for the Humanities, University of Washington, Seattle, Occasional Papers, no. 1,

2000.

5 Diane Arbus, eds. Doon Arbus, and

Marvin Israel...