Capodimonte Models and Miniatures

If success is measured by lasting name recognition, Capodimonte porcelain would seem to be in the same league as such makers as Meissen, Sèvres and Wedgwood. Early examples of Capodimonte lamps — as well as the Italian manufacturer’s celebrated porcelain vases, figurines and sculptures — can be hard to come by, but the best later pieces possess the same over-the-top charm.

The Real Fabbrica (“royal factory”) di Capodimonte hasn’t actually produced porcelain since the early 19th century, when Charles’s son Ferdinand sold it. Although secondary manufacturers have built upon the aesthetic and kept the name alive, some connoisseurs of the royal product feel these pieces should be labeled “in the style of” Capodimonte.

The timeline of royal Capodimonte porcelain is decidedly brief. From beginning to end, its manufacture lasted approximately 75 years. King Charles VII of Naples, who founded the manufactory in 1743, began experimenting with porcelain around 1738, the year he married Maria Amalia of Saxony. No coincidence there. His new bride was the granddaughter of Augustus the Strong, Elector of Saxony and founder of Meissen, the first European hard-paste porcelain manufactory. Her dowry included 17 Meissen table services.

Struck by porcelain fever, Charles built a dedicated facility on top of a hill (capo di monte) overlooking Naples. He financed expeditions to search for the right clay. He hired chemists and artisans to experiment. His earliest successes were small white snuffboxes and vases, although efforts soon progressed to full sets of tableware, decorative objects and stylized figurines of peasants and theatrical personalities.

In 1759, Charles succeeded to the throne of Spain. He moved the manufactory with him — including 40 workers and 4 tons of clay — and continued operations in Madrid. Twelve years later, his son Ferdinand IV, who inherited the throne of Naples, built a new factory there that became known for distinctly rococo designs.

The Napoleonic wars interrupted production, and around 1807, oversight of the royal factories was transferred to a franchisee named Giovanni Poulard-Prad.

Beginning in the mid-18th century, porcelain made by Charles’s factory was stamped with a fleur-de-lis, usually in underglaze blue. Pieces from Ferdinand’s were stamped with a Neapolitan N topped by a crown. When secondary manufacturers began production, they retained this mark, in multiple variations. The value of these later 19th- and 20th-century pieces is determined by the quality, not the Capodimonte porcelain marks.

Find antique and vintage Capodimonte porcelain for sale on 1stDibs.

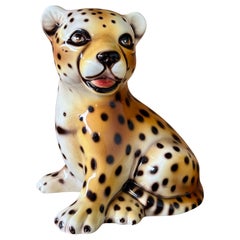

Mid-20th Century Italian Regency Capodimonte Models and Miniatures

Porcelain

Late 20th Century Italian Mid-Century Modern Capodimonte Models and Miniatures

Ceramic, Wood

Mid-20th Century North American Mid-Century Modern Capodimonte Models and Miniatures

Bronze

1960s American American Classical Vintage Capodimonte Models and Miniatures

Textile, Resin

1920s French Folk Art Vintage Capodimonte Models and Miniatures

Wire

1970s German American Classical Vintage Capodimonte Models and Miniatures

Blown Glass

Late 20th Century Italian Renaissance Revival Capodimonte Models and Miniatures

Porcelain, Mahogany

Mid-20th Century Japanese Anglo-Japanese Capodimonte Models and Miniatures

Textile

Late 20th Century Japanese Capodimonte Models and Miniatures

Metal

Early 20th Century German Folk Art Capodimonte Models and Miniatures

Plastic

1960s Italian Mid-Century Modern Vintage Capodimonte Models and Miniatures

Ceramic

1970s Italian Vintage Capodimonte Models and Miniatures

Ceramic

1950s Italian Vintage Capodimonte Models and Miniatures

Wood