Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

to

2

23

1

Overall Width

to

Overall Height

to

23

1

1

26

1,220

972

913

839

26

25

19

7

2

2

2

2

2

1

1

1

1

1

1

21

4

1

23

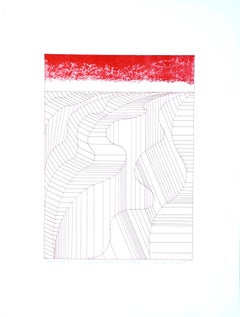

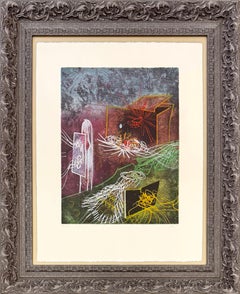

Artist: Costantino Persiani

First Landscape Structure - Original Etching by Costantino Persiani - 1971

By Costantino Persiani

Located in Roma, IT

Hand Signed.

Artist's Proofs in Arabic and Roman Numbers.

Category

1970s Contemporary Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

Materials

Etching

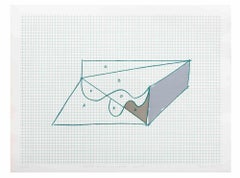

Sketch for an Impossible Project - Lithograph by Costantino Persiani - 1971

By Costantino Persiani

Located in Roma, IT

Lithograph realized by Costantino Persiani in 1971.

Limited Edition of 120.

Excellent condition.

Category

1970s Contemporary Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

Materials

Lithograph

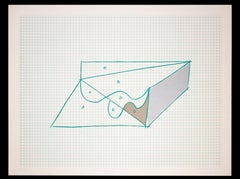

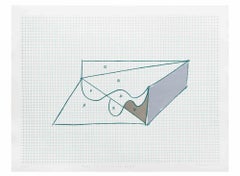

Sketch for an impossible project - Original Litho by Costantino Persiani - 1971

By Costantino Persiani

Located in Roma, IT

Limited edition of 120 prints, numbered and hand signed.

Excellent condition.

Category

1970s Contemporary Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

Materials

Lithograph

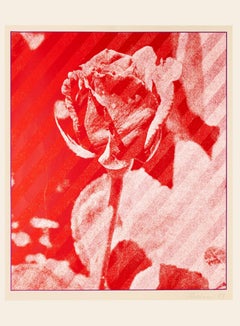

The Rose - Original Screen Print by Costantino Persiani - 1973

By Costantino Persiani

Located in Roma, IT

The Rose is an Original print screen on cardboard by Costantino Persiani in 1973.

Hand-signed and dated on the lower right.

Good conditions.

Numbered, edition 73/210.

Dimension: ...

Category

1970s Contemporary Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

Materials

Screen

Sketch for an Impossible Project- Lithograph by Costantino Persiani - 1971

By Costantino Persiani

Located in Roma, IT

Lithograph realized by Costantino Persiani in 1971.

Limited Edition of 120.

Excellent condition.

Category

1970s Contemporary Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

Materials

Lithograph

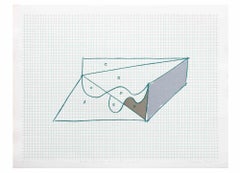

Sketch for an Impossible Project - Lithograph by Costantino Persiani - 1971

By Costantino Persiani

Located in Roma, IT

Lithograph realized by Costantino Persiani in 1971.

Limited Edition of 120.

Excellent condition.

Category

1970s Contemporary Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

Materials

Lithograph

Sketch for an Impossible Project - Original Litho by Costantino Persiani - 1971

By Costantino Persiani

Located in Roma, IT

Lithograph realized by Costantino Persiani in 1971.

Limited Edition of 120.

Excellent condition.

Category

1970s Contemporary Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

Materials

Lithograph

Sketch for an Impossible Project - Original Litho by Costantino Persiani - 1971

By Costantino Persiani

Located in Roma, IT

Lithograph realized by Costantino Persiani in 1971.

Limited Edition of 120.

Excellent condition.

Category

1970s Contemporary Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

Materials

Lithograph

Sketch for an Impossible Project - Lithograph by Costantino Persiani - 1971

By Costantino Persiani

Located in Roma, IT

Lithograph realized by Costantino Persiani in 1971.

Limited Edition of 120.

Excellent condition.

Category

1970s Contemporary Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

Materials

Lithograph

Sketch for an Impossible Project - Original Litho by Costantino Persiani - 1971

By Costantino Persiani

Located in Roma, IT

Lithograph realized by Costantino Persiani in 1971.

Limited Edition of 120.

Excellent condition.

Category

1970s Contemporary Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

Materials

Lithograph

Sketch for an Impossible Project - Lithograph by Costantino Persiani - 1971

By Costantino Persiani

Located in Roma, IT

Lithograph realized by Costantino Persiani in 1971.

Limited Edition of 120.

Excellent condition.

Category

1970s Contemporary Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

Materials

Lithograph

Sketch for an Impossible Project - Original Litho by Costantino Persiani - 1971

By Costantino Persiani

Located in Roma, IT

Lithograph realized by Costantino Persiani in 1971.

Limited Edition of 120.

Excellent condition.

Category

1970s Contemporary Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

Materials

Lithograph

Sketch for an Impossible Project - Litho by Costantino Persiani - 1971

By Costantino Persiani

Located in Roma, IT

Lithograph realized by Costantino Persiani in 1971.

Limited Edition of 120.

Excellent condition.

Category

1970s Contemporary Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

Materials

Lithograph

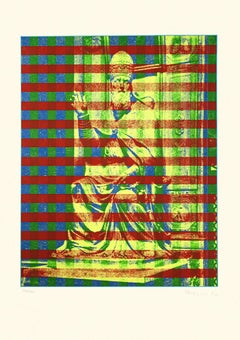

Pope on the throne I - Screen Print by Costantino Persiani - 1970s

By Costantino Persiani

Located in Roma, IT

This original serigraph is hand signed, numbered and dated by the artist Costantino Persiani. This original print is from an edition of 230 prints. Very good conditions.

Category

1970s Modern Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

Materials

Screen

Sketch for an Impossible Project - Lithograph by Costantino Persiani - 1971

By Costantino Persiani

Located in Roma, IT

Lithograph realized by Costantino Persiani in 1971.

Limited Edition of 120.

Excellent condition.

Category

1970s Contemporary Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

Materials

Lithograph

Sketch for an Impossible Project - Lithograph by Costantino Persiani - 1971

By Costantino Persiani

Located in Roma, IT

Lithograph realized by Costantino Persiani in 1971.

Limited Edition of 120.

Excellent condition.

Category

1970s Contemporary Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

Materials

Lithograph

Sketch for an impossible project - Litho by Costantino Persiani - 1971

By Costantino Persiani

Located in Roma, IT

Limited edition of 120 prints, numbered and hand signed.

Category

20th Century Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

Materials

Lithograph

Saint Peter - Screen Print by Costantino Persiani - 1973

By Costantino Persiani

Located in Roma, IT

Saint Peter is an original screen on cardboard by Costantino Persiani in 1973.

Hand-signed and dated on the lower right.

Good conditions. Numbered, edition 40/225.

Dimension: 86 x 62 cm.

Beautiful artwork representing the St. Peter in the Vatican with Corinthial elements and decorations above the big...

Category

1970s Contemporary Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

Materials

Screen

Rose - Screen Print by Costantino Persiani - 1973

By Costantino Persiani

Located in Roma, IT

This original serigraph is hand signed, numbered and dated by the artist Costantino Persiani. This original print is from an edition of 290 prints. Very good conditions.

Category

1970s Contemporary Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

Materials

Screen

Sketch for an Impossible Project - Original Litho by Costantino Persiani - 1971

By Costantino Persiani

Located in Roma, IT

Lithograph realized by Costantino Persiani in 1971.

Limited Edition of 120.

Excellent condition.

Category

1970s Contemporary Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

Materials

Lithograph

Sketch for an Impossible Project - Lithograph by Costantino Persiani - 1971

By Costantino Persiani

Located in Roma, IT

Lithograph realized by Costantino Persiani in 1971.

Limited Edition of 120.

Excellent condition.

Category

1970s Contemporary Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

Materials

Lithograph

Sketch for an Impossible Project - Lithograph by Costantino Persiani - 1971

By Costantino Persiani

Located in Roma, IT

Lithograph realized by Costantino Persiani in 1971.

Limited Edition of 120.

Excellent condition.

Category

1970s Contemporary Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

Materials

Lithograph

Sketch for an Impossible Project - Lithograph by Costantino Persiani - 1971

By Costantino Persiani

Located in Roma, IT

Lithograph realized by Costantino Persiani in 1971.

Limited Edition of 120.

Excellent condition.

Category

1970s Contemporary Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

Materials

Lithograph

Sketch for an Impossible Project - Lithograph by Costantino Persiani - 1971

By Costantino Persiani

Located in Roma, IT

Lithograph realized by Costantino Persiani in 1971.

Limited Edition of 120.

Excellent condition.

Category

1970s Contemporary Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

Materials

Lithograph

Sketch for an Impossible Project - Lithograph by Costantino Persiani - 1971

By Costantino Persiani

Located in Roma, IT

Lithograph realized by Costantino Persiani in 1971.

Limited Edition of 120.

Excellent condition.

Category

1970s Abstract Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

Materials

Lithograph

Sketch for an Impossible Project - Lithograph by Costantino Persiani - 1971

By Costantino Persiani

Located in Roma, IT

Lithograph realized by Costantino Persiani in 1971.

Limited Edition of 120.

Excellent condition.

Category

1970s Contemporary Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

Materials

Lithograph

Related Items

L

Explosion Qui Eclaire Mon Abime (framed signed aquatint and etching)

By Roberto Matta

Located in Aventura, FL

Aquatint and etching on paper. Hand signed lower right by Roberto Matta. Hand numbered 90/100 lower left. Image size: 14.1 x 18.6 inches. Sheet size: 26 x 19.6 inches. Frame siz...

Category

Early 2000s Contemporary Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

Materials

Paper, Etching, Aquatint

$1,500 Sale Price

25% Off

H 35.25 in W 28.75 in D 1 in

Waiting /// Contemporary Pop Art Interior Figurative Sofa Colorful Screenprint

By Dan May

Located in Saint Augustine, FL

Artist: Dan May (American, 1955-)

Title: "Waiting"

*Signed and numbered by May in pencil lower left

Year: 1986

Medium: Original Screenprint on unbranded soft-c...

Category

1980s Contemporary Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

Materials

Screen

$500

H 15.38 in W 12.32 in

Vase (2)

By Yayoi Kusama

Located in Bristol, GB

Lithograph

Edition 14 of 50

44.6 x 31.7 cm (17.5 x 12.4 in)

Signed, numbered, dated and titled on the front

Artwork in excellent condition. Minor imperfections may appear due to the ...

Category

1990s Contemporary Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

Materials

Lithograph

Running the Dog /// Contemporary Pop Art Screenprint Lady Animal Pet Walk Funny

By Dan May

Located in Saint Augustine, FL

Artist: Dan May (American, 1955-)

Title: "Running the Dog"

*Signed and numbered by May in pencil lower left

Year: 1984

Medium: Original Screenprint on unbranded white wove paper

Limited edition: 151/175

Printer: the artist May himself, Oakland, CA

Publisher: the artist May himself, Oakland, CA

Sheet size: 21" x 21"

Image size: 12.88" x 15.13"

Condition: In excellent condition

Notes:

Titled and dated by May in pencil lower right.

Biography:

Dan May is an American painter and printmaker born on March 11, 1955 in San Francisco, CA. Raised in aesthetic surroundings heavily influenced by his architect father, May grew up learning to view all things with an eye for design, color, and shape. At age 5, he remembers his father cutting up a book of drawings by Henri Matisse and hanging them on the walls of their home. The French master Matisse as well as Richard Diebenkorn and David Hockney are his favorite art influences. He began his first attempts at painting at age 15, and later began to experiment with printmaking, teaching himself various techniques such as woodblock printing, etching, silkscreen printing, and monoprinting.

Monoprinting soon became May's medium of choice due to its wide range of expression and spontaneity that he felt other techniques lacked. May - "With monoprinting, you can only work a piece for as a long as the paint stays wet, so the resulting print has a feeling of movement and immediacy. I also like how monoprinting allows the brush strokes to transfer a transparent light quality to the print. For me, this is a technique that bridges...

Category

1980s Contemporary Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

Materials

Screen

Fantasy, Japanese, limited edition lithograph, black, white, red, signed, titled

By Toko Shinoda

Located in Santa Fe, NM

Fantasy, Japanese, limited edition lithograph, black, white, red, signed, titled

Shinoda's works have been collected by public galleries and museums, including the Museum of Modern Art, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Brooklyn Museum and Metropolitan Museum (all in New York City), the National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo, the British Museum in London, the Art Institute of Chicago, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery of the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C., the Singapore Art Museum, the National Museum of Singapore, the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo, Netherlands, the Albright–Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, New York, the Cincinnati Art Museum, and the Yale University Art Gallery in New Haven, Connecticut.

New York Times Obituary, March 3, 2021 by Margalit Fox, Alex Traub contributed reporting.

Toko Shinoda, one of the foremost Japanese artists of the 20th century, whose work married the ancient serenity of calligraphy with the modernist urgency of Abstract Expressionism, died on Monday at a hospital in Tokyo. She was 107.

Her death was announced by her gallerist in the United States.

A painter and printmaker, Ms. Shinoda attained international renown at midcentury and remained sought after by major museums and galleries worldwide for more than five decades.

Her work has been exhibited at, among other places, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art in New York; the Art Institute of Chicago; the British Museum; and the National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo. Private collectors include the Japanese imperial family.

Writing about a 1998 exhibition of Ms. Shinoda’s work at a London gallery, the British newspaper The Independent called it “elegant, minimal and very, very composed,” adding, “Her roots as a calligrapher are clear, as are her connections with American art of the 1950s, but she is quite obviously a major artist in her own right.”

As a painter, Ms. Shinoda worked primarily in sumi ink, a solid form of ink, made from soot pressed into sticks, that has been used in Asia for centuries.

Rubbed on a wet stone to release their pigment, the sticks yield a subtle ink that, because it is quickly imbibed by paper, is strikingly ephemeral. The sumi artist must make each brush stroke with all due deliberation, as the nature of the medium precludes the possibility of reworking even a single line.

“The color of the ink which is produced by this method is a very delicate one,” Ms. Shinoda told The Business Times of Singapore in 2014. “It is thus necessary to finish one’s work very quickly. So the composition must be determined in my mind before I pick up the brush. Then, as they say, the painting just falls off the brush.”

Ms. Shinoda painted almost entirely in gradations of black, with occasional sepias and filmy blues. The ink sticks she used had been made for the great sumi artists of the past, some as long as 500 years ago.

Her line — fluid, elegant, impeccably placed — owed much to calligraphy. She had been rigorously trained in that discipline from the time she was a child, but she had begun to push against its confines when she was still very young.

Deeply influenced by American Abstract Expressionists like Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and Robert Motherwell, whose work she encountered when she lived in New York in the late 1950s, Ms. Shinoda shunned representation.

“If I have a definite idea, why paint it?,” she asked in an interview with United Press International in 1980. “It’s already understood and accepted. A stand of bamboo is more beautiful than a painting could be. Mount Fuji is more striking than any possible imitation.”

Spare and quietly powerful, making abundant use of white space, Ms. Shinoda’s paintings are done on traditional Chinese and Japanese papers, or on backgrounds of gold, silver or platinum leaf.

Often asymmetrical, they can overlay a stark geometric shape with the barest calligraphic strokes. The combined effect appears to catch and hold something evanescent — “as elusive as the memory of a pleasant scent or the movement of wind,” as she said in a 1996 interview.

Ms. Shinoda’s work also included lithographs; three-dimensional pieces of wood and other materials; and murals in public spaces, including a series made for the Zojoji Temple in Tokyo.

The fifth of seven children of a prosperous family, Ms. Shinoda was born on March 28, 1913, in Dalian, in Manchuria, where her father, Raijiro, managed a tobacco plant. Her mother, Joko, was a homemaker. The family returned to Japan when she was a baby, settling in Gifu, midway between Kyoto and Tokyo.

One of her father’s uncles, a sculptor and calligrapher, had been an official seal carver to the Meiji emperor. He conveyed his love of art and poetry to Toko’s father, who in turn passed it to Toko.

“My upbringing was a very traditional one, with relatives living with my parents,” she said in the U.P.I. interview. “In a scholarly atmosphere, I grew up knowing I wanted to make these things, to be an artist.”

She began studying calligraphy at 6, learning, hour by hour, impeccable mastery over line. But by the time she was a teenager, she had begun to seek an artistic outlet that she felt calligraphy, with its centuries-old conventions, could not afford.

“I got tired of it and decided to try my own style,” Ms. Shinoda told Time magazine in 1983. “My father always scolded me for being naughty and departing from the traditional way, but I had to do it.”

Moving to Tokyo as a young adult, Ms. Shinoda became celebrated throughout Japan as one of the country’s finest living calligraphers, at the time a signal honor for a woman. She had her first solo show in 1940, at a Tokyo gallery.

During World War II, when she forsook the city for the countryside near Mount Fuji, she earned her living as a calligrapher, but by the mid-1940s she had started experimenting with abstraction. In 1954 she began to achieve renown outside Japan with her inclusion in an exhibition of Japanese calligraphy at MoMA.

In 1956, she traveled to New York. At the time, unmarried Japanese women could obtain only three-month visas for travel abroad, but through zealous renewals, Ms. Shinoda managed to remain for two years.

She met many of the titans of Abstract Expressionism there, and she became captivated by their work.

“When I was in New York in the ’50s, I was often included in activities with those artists, people like Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock, Motherwell and so forth,” she said in a 1998 interview with The Business Times. “They were very generous people, and I was often invited to visit their studios, where we would share ideas and opinions on our work. It was a great experience being together with people who shared common feelings.”

During this period, Ms. Shinoda’s work was sold in the United States by Betty Parsons, the New York dealer who represented Pollock, Rothko and many of their contemporaries.

Returning to Japan, Ms. Shinoda began to fuse calligraphy and the Expressionist aesthetic in earnest. The result was, in the words of The Plain Dealer of Cleveland in 1997, “an art of elegant simplicity and high drama.”

Among Ms. Shinoda’s many honors, she was depicted, in 2016, on a Japanese postage stamp. She is the only Japanese artist to be so honored during her lifetime.

No immediate family members survive.

When she was quite young and determined to pursue a life making art, Ms. Shinoda made the decision to forgo the path that seemed foreordained for women of her generation.

“I never married and have no children,” she told The Japan Times in 2017. “And I suppose that it sounds strange to think that my paintings are in place of them — of course they are not the same thing at all. But I do say, when paintings that I have made years ago are brought back into my consciousness, it seems like an old friend, or even a part of me, has come back to see me.”

Works of a Woman's Hand

Toko Shinoda bases new abstractions on ancient calligraphy

Down a winding side street in the Aoyama district, western Tokyo. into a chunky white apartment building, then up in an elevator small enough to make a handful of Western passengers friends or enemies for life. At the end of a hall on the fourth floor, to the right, stands a plain brown door. To be admitted is to go through the looking glass. Sayonara today. Hello (Konichiwa) yesterday and tomorrow.

Toko Shinoda, 70, lives and works here. She can be, when she chooses, on e of Japans foremost calligraphers, master of an intricate manner of writing that traces its lines back some 3,000 years to ancient China. She is also an avant-garde artist of international renown, whose abstract paintings and lithographs rest in museums around the world. These diverse talents do not seem to belong in the same epoch. Yet they have somehow converged in this diminutive woman who appears in her tiny foyer, offering slippers and ritual bows of greeting.

She looks like someone too proper to chip a teacup, never mind revolutionize an old and hallowed art form She wears a blue and white kimono of her own design. Its patterns, she explains, are from Edo, meaning the period of the Tokugawa shoguns, before her city was renamed Tokyo in 1868. Her black hair is pulled back from her face, which is virtually free of lines and wrinkles. except for the gold-rimmed spectacles perched low on her nose (this visionary is apparently nearsighted). Shinoda could have stepped directly from a 19th century Meji print.

Her surroundings convey a similar sense of old aesthetics, a retreat in the midst of a modern, frenetic city. The noise of the heavy traffic on a nearby elevated highway sounds at this height like distant surf. delicate bamboo shades filter the daylight. The color arrangement is restful: low ceilings of exposed wood, off-white walls, pastel rugs of blue, green and gray.

It all feels so quintessentially Japanese that Shinoda’s opening remarks come as a surprise. She points out (through a translator) that she was not born in Japan at all but in Darien, Manchuria. Her father had been posted there to manage a tobacco company under the aegis of the occupying Japanese forces, which seized the region from Russia in 1905. She says,”People born in foreign places are very free in their thinking, not restricted” But since her family went back to Japan in 1915, when she was two, she could hardly remember much about a liberated childhood? She answers,”I think that if my mother had remained in Japan, she would have been an ordinary Japanese housewife. Going to Manchuria, she was able to assert her own personality, and that left its mark on me.”

Evidently so. She wears her obi low on the hips, masculine style. The Porcelain aloofness she displays in photographs shatters in person. Her speech is forceful, her expression animated and her laugh both throaty and infectious. The hand she brings to her mouth to cover her amusement (a traditional female gesture of modesty) does not stand a chance.

Her father also made a strong impression on the fifth of his seven children:”He came from a very old family, and he was quite strict in some ways and quite liberal in others.” He owned one of the first three bicycles ever imported to Japan and tinkered with it constantly He also decided that his little daughter would undergo rigorous training in a procrustean antiquity.

“I was forced to study from age six on to learn calligraphy,” Shinoda says, The young girl dutifully memorized and copied the accepted models. In one sense, her father had pushed her in a promising direction, one of the few professional fields in Japan open to females. Included among the ancient terms that had evolved around calligraphy was onnade, or woman's writing.

Heresy lay ahead. By the time she was 15, she had already been through nine years of intensive discipline, “I got tired of it and decided to try my own style. My father always scolded me for being naughty and departing from the traditional way, but I had to do it.”

She produces a brush and a piece of paper to demonstrate the nature of her rebellion. “This is kawa, the accepted calligraphic character for river,” she says, deftly sketching three short vertical strokes. “But I wanted to use more than three lines to show the force of the river.” Her brush flows across the white page, leaving a recognizable river behind, also flowing.” The simple kawa in the traditional language was not enough for me. I wanted to find a new symbol to express the word river.”

Her conviction grew that ink could convey the ineffable, the feeling, "as she says, of wind blowing softly.” Another demonstration. She goes to the sliding wooden door of an anteroom and disappears in back of it; the only trace of her is a triangular swatch of the right sleeve of her kimono, which she has arranged for that purpose. A realization dawns. The task of this artist is to paint that three sided pattern so that the invisible woman attached to it will be manifest to all viewers.

Gen, painted especially for TIME, shows Shinoda’s theory in practice. She calls the work “my conception of Japan in visual terms.” A dark swath at the left, punctuated by red, stands for history. In the center sits a Chinese character gen, which means in the present or actuality. A blank pattern at the right suggests an unknown future.

Once out of school, Shinoda struck off on a path significantly at odds with her culture. She recognized marriage for what it could mean to her career (“a restriction”) and decided against it. There was a living to be earned by doing traditional calligraphy:she used her free time to paint her variations. In 1940 a Tokyo gallery exhibited her work. (Fourteen years would pass before she got a second show.)War came, and bad times for nearly everyone, including the aspiring artist , who retreated to a rural area near Mount Fuji and traded her kimonos for eggs.

In 1954 Shinoda’s work was included in a group exhibit at New York City’s Museum of Modern Art. Two years later, she overcame bureaucratic obstacles to visit the U.S.. Unmarried Japanese women are allowed visas for only three months, patiently applying for two-month extensions, one at a time, Shinoda managed to travel the country for two years. She pulls out a scrapbook from this period. Leafing through it, she suddenly raises a hand and touches her cheek:”How young I looked!” An inspection is called for. The woman in the grainy, yellowing newspaper photograph could easily be the on e sitting in this room. Told this, she nods and smiles. No translation necessary.

Her sojourn in the U.S. proved to be crucial in the recognition and development of Shinoda’s art. Celebrities such as actor Charles Laughton and John Lewis of the Modern Jazz Quartet bought her paintings and spread the good word. She also saw the works of the abstract expressionists, then the rage of the New York City art world, and realized that these Western artists, coming out of an utterly different tradition, were struggling toward the same goal that had obsessed her. Once she was back home, her work slowly made her famous.

Although Shinoda has used many materials (fabric, stainless steel, ceramics, cement), brush and ink remain her principal means of expression. She had said, “As long as I am devoted to the creation of new forms, I can draw even with muddy water.” Fortunately, she does not have to. She points with evident pride to her ink stone, a velvety black slab of rock, with an indented basin, that is roughly a foot across and two feet long. It is more than 300 years old. Every working morning, Shinoda pours about a third of a pint of water into it, then selects an ink stick from her extensive collection, some dating back to China’s Ming dynasty. Pressing stick against stone, she begins rubbing. Slowly, the dried ink dissolves in the water and becomes ready for the brush. So two batches of sumi (India ink) are exactly alike; something old, something new. She uses color sparingly. Her clear preference is black and all its gradations. “In some paintings, sumi expresses blue better than blue.”

It is time to go downstairs to the living quarters. A niece, divorced and her daughter,10,stay here with Shinoda; the artist who felt forced to renounce family and domesticity at the outset of her career seems welcome to it now. Sake is offered, poured into small cedar boxes and happily accepted. Hold carefully. Drink from a corner. Ambrosial. And just right for the surroundings and the hostess. A conservative renegade; a liberal traditionalist; a woman steeped in the male-dominated conventions that she consistently opposed. Her trail blazing accomplishments are analogous to Picasso’s.

When she says goodbye, she bows. --by Paul Gray...

Category

1990s Contemporary Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

Materials

Lithograph

Tableau, Japanese, limited edition lithograph, black, white, red, signed, number

By Toko Shinoda

Located in Santa Fe, NM

Tableau, Japanese, limited edition lithograph, black, white, red, signed, number

Shinoda's works have been collected by public galleries and museums, including the Museum of Modern Art, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Brooklyn Museum and Metropolitan Museum (all in New York City), the National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo, the British Museum in London, the Art Institute of Chicago, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery of the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C., the Singapore Art Museum, the National Museum of Singapore, the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo, Netherlands, the Albright–Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, New York, the Cincinnati Art Museum, and the Yale University Art Gallery in New Haven, Connecticut.

New York Times Obituary, March 3, 2021 by Margalit Fox, Alex Traub contributed reporting.

Toko Shinoda, one of the foremost Japanese artists of the 20th century, whose work married the ancient serenity of calligraphy with the modernist urgency of Abstract Expressionism, died on Monday at a hospital in Tokyo. She was 107.

Her death was announced by her gallerist in the United States.

A painter and printmaker, Ms. Shinoda attained international renown at midcentury and remained sought after by major museums and galleries worldwide for more than five decades.

Her work has been exhibited at, among other places, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art in New York; the Art Institute of Chicago; the British Museum; and the National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo. Private collectors include the Japanese imperial family.

Writing about a 1998 exhibition of Ms. Shinoda’s work at a London gallery, the British newspaper The Independent called it “elegant, minimal and very, very composed,” adding, “Her roots as a calligrapher are clear, as are her connections with American art of the 1950s, but she is quite obviously a major artist in her own right.”

As a painter, Ms. Shinoda worked primarily in sumi ink, a solid form of ink, made from soot pressed into sticks, that has been used in Asia for centuries.

Rubbed on a wet stone to release their pigment, the sticks yield a subtle ink that, because it is quickly imbibed by paper, is strikingly ephemeral. The sumi artist must make each brush stroke with all due deliberation, as the nature of the medium precludes the possibility of reworking even a single line.

“The color of the ink which is produced by this method is a very delicate one,” Ms. Shinoda told The Business Times of Singapore in 2014. “It is thus necessary to finish one’s work very quickly. So the composition must be determined in my mind before I pick up the brush. Then, as they say, the painting just falls off the brush.”

Ms. Shinoda painted almost entirely in gradations of black, with occasional sepias and filmy blues. The ink sticks she used had been made for the great sumi artists of the past, some as long as 500 years ago.

Her line — fluid, elegant, impeccably placed — owed much to calligraphy. She had been rigorously trained in that discipline from the time she was a child, but she had begun to push against its confines when she was still very young.

Deeply influenced by American Abstract Expressionists like Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and Robert Motherwell, whose work she encountered when she lived in New York in the late 1950s, Ms. Shinoda shunned representation.

“If I have a definite idea, why paint it?,” she asked in an interview with United Press International in 1980. “It’s already understood and accepted. A stand of bamboo is more beautiful than a painting could be. Mount Fuji is more striking than any possible imitation.”

Spare and quietly powerful, making abundant use of white space, Ms. Shinoda’s paintings are done on traditional Chinese and Japanese papers, or on backgrounds of gold, silver or platinum leaf.

Often asymmetrical, they can overlay a stark geometric shape with the barest calligraphic strokes. The combined effect appears to catch and hold something evanescent — “as elusive as the memory of a pleasant scent or the movement of wind,” as she said in a 1996 interview.

Ms. Shinoda’s work also included lithographs; three-dimensional pieces of wood and other materials; and murals in public spaces, including a series made for the Zojoji Temple in Tokyo.

The fifth of seven children of a prosperous family, Ms. Shinoda was born on March 28, 1913, in Dalian, in Manchuria, where her father, Raijiro, managed a tobacco plant. Her mother, Joko, was a homemaker. The family returned to Japan when she was a baby, settling in Gifu, midway between Kyoto and Tokyo.

One of her father’s uncles, a sculptor and calligrapher, had been an official seal carver to the Meiji emperor. He conveyed his love of art and poetry to Toko’s father, who in turn passed it to Toko.

“My upbringing was a very traditional one, with relatives living with my parents,” she said in the U.P.I. interview. “In a scholarly atmosphere, I grew up knowing I wanted to make these things, to be an artist.”

She began studying calligraphy at 6, learning, hour by hour, impeccable mastery over line. But by the time she was a teenager, she had begun to seek an artistic outlet that she felt calligraphy, with its centuries-old conventions, could not afford.

“I got tired of it and decided to try my own style,” Ms. Shinoda told Time magazine in 1983. “My father always scolded me for being naughty and departing from the traditional way, but I had to do it.”

Moving to Tokyo as a young adult, Ms. Shinoda became celebrated throughout Japan as one of the country’s finest living calligraphers, at the time a signal honor for a woman. She had her first solo show in 1940, at a Tokyo gallery.

During World War II, when she forsook the city for the countryside near Mount Fuji, she earned her living as a calligrapher, but by the mid-1940s she had started experimenting with abstraction. In 1954 she began to achieve renown outside Japan with her inclusion in an exhibition of Japanese calligraphy at MoMA.

In 1956, she traveled to New York. At the time, unmarried Japanese women could obtain only three-month visas for travel abroad, but through zealous renewals, Ms. Shinoda managed to remain for two years.

She met many of the titans of Abstract Expressionism there, and she became captivated by their work.

“When I was in New York in the ’50s, I was often included in activities with those artists, people like Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock, Motherwell and so forth,” she said in a 1998 interview with The Business Times. “They were very generous people, and I was often invited to visit their studios, where we would share ideas and opinions on our work. It was a great experience being together with people who shared common feelings.”

During this period, Ms. Shinoda’s work was sold in the United States by Betty Parsons, the New York dealer who represented Pollock, Rothko and many of their contemporaries.

Returning to Japan, Ms. Shinoda began to fuse calligraphy and the Expressionist aesthetic in earnest. The result was, in the words of The Plain Dealer of Cleveland in 1997, “an art of elegant simplicity and high drama.”

Among Ms. Shinoda’s many honors, she was depicted, in 2016, on a Japanese postage stamp. She is the only Japanese artist to be so honored during her lifetime.

No immediate family members survive.

When she was quite young and determined to pursue a life making art, Ms. Shinoda made the decision to forgo the path that seemed foreordained for women of her generation.

“I never married and have no children,” she told The Japan Times in 2017. “And I suppose that it sounds strange to think that my paintings are in place of them — of course they are not the same thing at all. But I do say, when paintings that I have made years ago are brought back into my consciousness, it seems like an old friend, or even a part of me, has come back to see me.”

Works of a Woman's Hand

Toko Shinoda bases new abstractions on ancient calligraphy

Down a winding side street in the Aoyama district, western Tokyo. into a chunky white apartment building, then up in an elevator small enough to make a handful of Western passengers friends or enemies for life. At the end of a hall on the fourth floor, to the right, stands a plain brown door. To be admitted is to go through the looking glass. Sayonara today. Hello (Konichiwa) yesterday and tomorrow.

Toko Shinoda, 70, lives and works here. She can be, when she chooses, on e of Japans foremost calligraphers, master of an intricate manner of writing that traces its lines back some 3,000 years to ancient China. She is also an avant-garde artist of international renown, whose abstract paintings and lithographs rest in museums around the world. These diverse talents do not seem to belong in the same epoch. Yet they have somehow converged in this diminutive woman who appears in her tiny foyer, offering slippers and ritual bows of greeting.

She looks like someone too proper to chip a teacup, never mind revolutionize an old and hallowed art form She wears a blue and white kimono of her own design. Its patterns, she explains, are from Edo, meaning the period of the Tokugawa shoguns, before her city was renamed Tokyo in 1868. Her black hair is pulled back from her face, which is virtually free of lines and wrinkles. except for the gold-rimmed spectacles perched low on her nose (this visionary is apparently nearsighted). Shinoda could have stepped directly from a 19th century Meji print.

Her surroundings convey a similar sense of old aesthetics, a retreat in the midst of a modern, frenetic city. The noise of the heavy traffic on a nearby elevated highway sounds at this height like distant surf. delicate bamboo shades filter the daylight. The color arrangement is restful: low ceilings of exposed wood, off-white walls, pastel rugs of blue, green and gray.

It all feels so quintessentially Japanese that Shinoda’s opening remarks come as a surprise. She points out (through a translator) that she was not born in Japan at all but in Darien, Manchuria. Her father had been posted there to manage a tobacco company under the aegis of the occupying Japanese forces, which seized the region from Russia in 1905. She says,”People born in foreign places are very free in their thinking, not restricted” But since her family went back to Japan in 1915, when she was two, she could hardly remember much about a liberated childhood? She answers,”I think that if my mother had remained in Japan, she would have been an ordinary Japanese housewife. Going to Manchuria, she was able to assert her own personality, and that left its mark on me.”

Evidently so. She wears her obi low on the hips, masculine style. The Porcelain aloofness she displays in photographs shatters in person. Her speech is forceful, her expression animated and her laugh both throaty and infectious. The hand she brings to her mouth to cover her amusement (a traditional female gesture of modesty) does not stand a chance.

Her father also made a strong impression on the fifth of his seven children:”He came from a very old family, and he was quite strict in some ways and quite liberal in others.” He owned one of the first three bicycles ever imported to Japan and tinkered with it constantly He also decided that his little daughter would undergo rigorous training in a procrustean antiquity.

“I was forced to study from age six on to learn calligraphy,” Shinoda says, The young girl dutifully memorized and copied the accepted models. In one sense, her father had pushed her in a promising direction, one of the few professional fields in Japan open to females. Included among the ancient terms that had evolved around calligraphy was onnade, or woman's writing.

Heresy lay ahead. By the time she was 15, she had already been through nine years of intensive discipline, “I got tired of it and decided to try my own style. My father always scolded me for being naughty and departing from the traditional way, but I had to do it.”

She produces a brush and a piece of paper to demonstrate the nature of her rebellion. “This is kawa, the accepted calligraphic character for river,” she says, deftly sketching three short vertical strokes. “But I wanted to use more than three lines to show the force of the river.” Her brush flows across the white page, leaving a recognizable river behind, also flowing.” The simple kawa in the traditional language was not enough for me. I wanted to find a new symbol to express the word river.”

Her conviction grew that ink could convey the ineffable, the feeling, "as she says, of wind blowing softly.” Another demonstration. She goes to the sliding wooden door of an anteroom and disappears in back of it; the only trace of her is a triangular swatch of the right sleeve of her kimono, which she has arranged for that purpose. A realization dawns. The task of this artist is to paint that three sided pattern so that the invisible woman attached to it will be manifest to all viewers.

Gen, painted especially for TIME, shows Shinoda’s theory in practice. She calls the work “my conception of Japan in visual terms.” A dark swath at the left, punctuated by red, stands for history. In the center sits a Chinese character gen, which means in the present or actuality. A blank pattern at the right suggests an unknown future.

Once out of school, Shinoda struck off on a path significantly at odds with her culture. She recognized marriage for what it could mean to her career (“a restriction”) and decided against it. There was a living to be earned by doing traditional calligraphy:she used her free time to paint her variations. In 1940 a Tokyo gallery exhibited her work. (Fourteen years would pass before she got a second show.)War came, and bad times for nearly everyone, including the aspiring artist , who retreated to a rural area near Mount Fuji and traded her kimonos for eggs.

In 1954 Shinoda’s work was included in a group exhibit at New York City’s Museum of Modern Art. Two years later, she overcame bureaucratic obstacles to visit the U.S.. Unmarried Japanese women are allowed visas for only three months, patiently applying for two-month extensions, one at a time, Shinoda managed to travel the country for two years. She pulls out a scrapbook from this period. Leafing through it, she suddenly raises a hand and touches her cheek:”How young I looked!” An inspection is called for. The woman in the grainy, yellowing newspaper photograph could easily be the on e sitting in this room. Told this, she nods and smiles. No translation necessary.

Her sojourn in the U.S. proved to be crucial in the recognition and development of Shinoda’s art. Celebrities such as actor Charles Laughton and John Lewis of the Modern Jazz Quartet bought her paintings and spread the good word. She also saw the works of the abstract expressionists, then the rage of the New York City art world, and realized that these Western artists, coming out of an utterly different tradition, were struggling toward the same goal that had obsessed her. Once she was back home, her work slowly made her famous.

Although Shinoda has used many materials (fabric, stainless steel, ceramics, cement), brush and ink remain her principal means of expression. She had said, “As long as I am devoted to the creation of new forms, I can draw even with muddy water.” Fortunately, she does not have to. She points with evident pride to her ink stone, a velvety black slab of rock, with an indented basin, that is roughly a foot across and two feet long. It is more than 300 years old. Every working morning, Shinoda pours about a third of a pint of water into it, then selects an ink stick from her extensive collection, some dating back to China’s Ming dynasty. Pressing stick against stone, she begins rubbing. Slowly, the dried ink dissolves in the water and becomes ready for the brush. So two batches of sumi (India ink) are exactly alike; something old, something new. She uses color sparingly. Her clear preference is black and all its gradations. “In some paintings, sumi expresses blue better than blue.”

It is time to go downstairs to the living quarters. A niece, divorced and her daughter,10,stay here with Shinoda; the artist who felt forced to renounce family and domesticity at the outset of her career seems welcome to it now. Sake is offered, poured into small cedar boxes and happily accepted. Hold carefully. Drink from a corner. Ambrosial. And just right for the surroundings and the hostess. A conservative renegade; a liberal traditionalist; a woman steeped in the male-dominated conventions that she consistently opposed. Her trail blazing accomplishments are analogous to Picasso’s.

When she says goodbye, she bows. --by Paul Gray...

Category

1990s Contemporary Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

Materials

Lithograph

No. I, from Natural History, Part I, Mushroom (Bastian 42), 1974, Lithograph

By Cy Twombly

Located in Bristol, GB

Collotype in colours with collage and hand-colouring

Edition 24 of 98

75.8 x 55.8 cm (29.8 x 22 in)

Signed with initials and numbered on the front

Condition upon request

Published by...

Category

1970s Contemporary Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

Materials

Lithograph

$18,507

H 29.85 in W 21.97 in

Yellow Mimosa, July 23, 2015 - Contemporary, 21st Century, Screenprint

By Donald Sultan

Located in Zug, CH

Donald Sultan, Yellow Mimosa, July 23,

Screenprint in colors with yellow flocking on 4-ply museum board.

Edition of 50.

81.3 x 114.3 cm (32.2 x 45.5 in)

Signed, dated, numbered, and titled accompanied by Certificate of Authenticity

Published by Lococo Fine Art, St. Louis.

In mint condition, as acquired from the publisher

PLEASE NOTE: Edition numbers could vary from the one shown in the pictures. The piece is offered unframed.

Sultan’s work incorporates basic geometric and organic forms with a formal purity that is both subtle and monumental. His images are weighty, with equal emphasis on both negative and positive areas. His powerfully sensual, fleshy object representations are rendered through a labor-intensive and unique method.

"The image in the front is very fragile, but it conveys the loaded meaning of everything that is contained in the painting." — Donald Sultan

This print of flowing yellow mimosa blossoms, which shows all the textural qualities that the artist excels at in his printmaking projects, is made with several layers of color silkscreen, some matte finish inks, and some glossy. Mimosas depicts the flowering plant Mimosa, which is also called the sensitive plant or sleepy plant. Sultan seems to have taken inspiration from the name with the dark black, chalky stems flowing down and covering most of the page and the clusters of white spots symbolizing the blossoms.

DONALD SULTAN

Donald Sultan (born 1951, Asheville, US) is a distinguished painter, sculptor, and printmaker, who rose to prominence in the late 1970s as part of the “New Image” movement. He is best known for the use of abstracted, geometric black forms against organic areas of bright color.

Donald Sultan (USA, born 1951) is a distinguished painter, sculptor, and printmaker, who rose to prominence in the late 1970s as part of the New Yorker “New Image” movement. He has a unique artistic method and innovative approach to traditional subject matter. Known as Abstract Representation, Donald Sultan´s art is characterized by the use of geometric black forms set against organic areas of bright color, thus bringing an abstract sensibility to his iconographic images of still life. Throughout his career he has revisited and reinvented still life, using images of lemons, poppies, playing cards, fruits, flowers, and other objects. Donald Sultan’s Lemons...

Category

2010s Contemporary Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

Materials

Screen

$8,043 Sale Price

32% Off

H 32.01 in W 45.01 in

"Irregular Arcs from Four Sides" signed etching with aquatint by Sol LeWitt

By Sol LeWitt

Located in Boca Raton, FL

"Irregular Arcs from Four Sides" colorful, geometric abstract etching with aquatint in colors on Somerset paper with full margins. Signed and numbered PP 2/3 in pencil on front lower...

Category

1990s Contemporary Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

Materials

Etching, Aquatint

I Love…

By David Shrigley

Located in Bristol, GB

4 colour screenprint on Somerset Tub Sized Satin White 410gsm

Edition 117 of 125

76 x 60 cm (29.9 x 23.6 in)

Signed, numbered and dated on the back

Mint. Minor imperfections may appe...

Category

21st Century and Contemporary Contemporary Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

Materials

Screen

Keith Haring Rain Dance 1985 (Keith Haring posters)

By Keith Haring

Located in NEW YORK, NY

Keith Haring Rain Dance 1985:

RARE original 1980s Keith Haring illustrated poster announcement for a legendary Keith Haring UNICEF benefit party at Larry Levan’s Paradise Garage in 1985. An event organized & curated by Keith Haring; with cohosts including Jean-Michel Basquiat, Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein & more. A event organized by Haring on behalf of UNICEF’s African Emergency Relief Fund. Beautifully combines Haring’s trademark kinetic figures set amidst a standout blue and black color-way. Rare.

Medium: Offset lithograph in colors on smooth wove paper. 1985.

Dimensions: 8.5 x 11 inches (folded open).

Fair overall vintage condition. Minor wear to center fold-line; minor separation to the mid far-left edge; surface loss lower left. Otherwise well-preserved.

Printed signature, ‘Keith Haring 1985’ on lower right from a scarce edition of unknown.

Looks fantastic framed.

More on Keith Haring Rain Dance:

Curated and organized by Keith Haring, Rain Dance was a 1985 benefit for UNICEF’s African Emergency Relief Fund. Participating artists famously included: Jean-Michel Basquiat, Larry Levan, Fred Brathwaite, Christo, Francesco Clemente, George Condo, Crash, Futura 2000, Jenny Holzer, John Lennon, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Mapplethorpe, Brice Marden, Robert Morris, Yoko Ono, Lee Quiñones, Robert Rauschenberg, Kenny Scharf, Julian Schnabel, Richard Serra, Cindy Sherman, Tseng Kwong Chi, and Andy Warhol.

_

Keith Haring (American, 1958–1990), a Neo-Pop and Graffiti artist, had a short but prolific career centered on a vision to unite “high art,” urban aesthetics, and public spaces using humorous, irreverent, and poignant works. Born in Pennsylvania, Haring attended the Ivy School of Art in Pittsburgh for two years, planning to become a commercial artist. He found this path unsatisfying, and instead chose to study at the School of Visual Arts in New York, where he met fellow artists Jean Michel Basquiat and Kenny Scharf. Haring immersed himself in the culture of the city’s streets and clubs, and, in 1980, began covering the blank billboards on subway station walls with his Subway drawings in chalk.

Haring’s bold public art attracted the attention of several galleries, and, by the early 1980s, he was painting Neo-Pop works and large murals full time. In an effort to make his art widely accessible, Haring opened the Pop Shop in 1986 in downtown New York, selling commercial items adorned with his signature, cartoonish imagery. Haring combined graffiti, hip-hop, and urban aesthetics, frequently depicting animals, figures, commercial icons, sexual imagery, and childlike motifs in pieces that were both playful and concerned with social issues.

His work became increasingly confrontational following his 1987 diagnosis of AIDS. Haring resolved to work harder than ever in his remaining years, creating pieces with a fervent speed and devoting his art to social action in addition to his personal expression. In 1989, he established the Keith Haring Foundation, whose goal is to promote art programs and public spaces for children, and to raise awareness about AIDS.

Haring died on February 16, 1990 in New York at the age of 31. In addition to hundreds of exhibitions held during his lifetime, Haring has been the subject of numerous retrospectives in New York, San Francisco, Paris, Tokyo, Los Angeles and Berlin since his death.

Related Categories:

Keith Haring posters. Keith Haring activist poster. Keith Haring Dancers. Street art. Graffiti. 1980s. Keith Haring Larry Levan. Keith Haring Paradise Garage...

Category

1980s Contemporary Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

Materials

Lithograph, Offset

The End of the Game Rare 1970s ICP print (Hand Signed, inscribed by Peter Beard)

By Peter Beard

Located in New York, NY

Peter Beard

The End of the Game (Hand Signed by Peter Beard), 1977

Offset Lithograph Poster (hand signed by Peter Beard and inscribed with a heart)

Han...

Category

1970s Contemporary Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

Materials

Lithograph, Offset

$2,000

H 27.5 in W 20.5 in

Previously Available Items

Saint Peter - Original Scree Print by Costantino Persiani - 1972

By Costantino Persiani

Located in Roma, IT

Saint Peter is an original screen print on cardboard by Costantino Persiani in 1972.

Hand-signed and dated on the lower right.

Good conditions.

Numbered, edition 204/230.

dimension: 89 x 63

Beautiful artwork representing the St. Peter in the Vatican with Corinthial elements and decorations above the big chair.

Category

1970s Contemporary Costantino Persiani Prints and Multiples

Materials

Screen

H 25.6 in W 20.08 in D 0.04 in

Costantino Persiani prints and multiples for sale on 1stDibs.

Find a wide variety of authentic Costantino Persiani prints and multiples available for sale on 1stDibs. If you’re browsing the collection of prints and multiples to introduce a pop of color in a neutral corner of your living room or bedroom, you can find work that includes elements of blue, orange, pink and other colors. You can also browse by medium to find art by Costantino Persiani in screen print, lithograph, etching and more. Much of the original work by this artist or collective was created during the 20th century and is mostly associated with the contemporary style. Not every interior allows for large Costantino Persiani prints and multiples, so small editions measuring 1 inch across are available. Customers who are interested in this artist might also find the work of Arnoldo Ciarrocchi, Ercole Pignatelli, and Edo Janich. Costantino Persiani prints and multiples prices can differ depending upon medium, time period and other attributes. On 1stDibs, the price for these items starts at $66 and tops out at $501, while the average work can sell for $267.