October 19, 2025Some interior designers rebuff the idea that they have a signature style, maintaining that each interior is unique because they design it to reflect their clients’ personal tastes and lifestyle choices. Sarah Solis has a different take on the issue.

She does not deny having a set of stylistic predilections. “I have always had a timeless approach, but I admire functionality and innovation. It’s really about balancing form and function, about warmth and how a space holds you,” says Solis, who also heads Galerie Solis, which produces a line of furniture that aligns with her timeless aesthetic and also deals in European textiles, art and vintage pieces, many available through her 1stDibs storefront.

Her work, she continues, is distinguished by “an overarching calm and an earthy palette. I also believe texture is how you experience a space, how it holds you. I love subtle stripes or a quiet gingham. And I love color drenching and using variations of a single color. It’s all a bit emotional.”

Almost every project Solis takes on contains these elements, yet each looks different from the one before. She achieves that neat trick by infusing her interiors with unique characteristics that create a subliminal narrative centered on, among other key factors, the clients’ personal background, their aspirations for their life and the architectural and geographic surroundings.

Philosopher and historian Hannah Arendt wrote that “storytelling reveals meaning without committing the error of defining it.” Solis’s interiors embody this concept by unfolding their narratives in ways that are not immediately obvious or predictable. We sense their very personal soulfulness without being able to put our finger on what exactly transmits that quality. “Emotions speak to story. Your spaces should make you feel something,” Solis says. “If you can connect to your emotions, you can build a story that is inspiring.”

It might be surprising, then, that Solis originally underestimated the power of conveying emotions and telling stories through design as a way of making a livelihood.

For years, she resisted becoming a designer. The daughter of a builder and musician father and a “fashion-obsessed” mother who made her own clothes, Solis was raised in a creative milieu. Her parents would often take her to look at houses her dad was working on. “I noticed a lot of architectural details early on,” recalls Solis, who in middle school was the only girl taking woodworking. “Design has been a lifelong passion. But I didn’t know I could make a career of it.”

Not sure how else to channel her interests, she earned a bachelor’s degree in interior design, then got a master’s in fine arts and art history. Her earlier woodworking classes, as well as a program in grad school run by a Japanese porcelain master, awakened in her an understanding of the storytelling potential of materials — how the way a wood or ceramic piece was created can live on in its finished form.

After college, she landed a job managing a photographer’s studio. Impressed with Solis’s flare for dressing and accessorizing, he asked her to style some of his fashion shoots. His clients, in turn, would often inquire about the stylist he used and began hiring Solis on a regular basis.

She spent the next dozen years as a fashion stylist for notable actors and musicians. “That slowly crept into consulting on how they should do their homes,” she says. Still, Solis resisted hanging up her design shingle.

It was only after she married Rennie Solis — a commercial photographer whose clients include such major companies as Apple, Sony, Nike and Google — that she came around to the idea. They bought a ramshackle house in Pasadena, renovated it and then sold it. Their social media posts about the project soon led to inquiries from prospective clients.

“We bought our next house in Glendale, and the same thing happened,” she recalls. “An actress bought it. Then, a musician saw an Instagram post of our third house [in Topanga] and offered us cash for it before it was even done. I realized I kept getting pulled into design. That’s when I made the decision to establish a firm.” The year was 2017.

Solis brought her diverse background and early professional experiences to bear on two recent Malibu projects — her own home and a residence that she designed for Baltimore Ravens offensive tackle Ronnie Stanley, who uses it as an offseason retreat — both of which also show off several of her signatures.

In each, the kitchen counters and backsplashes are of figured stones: Calacatta Viola marble at her home and, at Stanley’s zen residence, Travertine limestone. “I love singular bold moments when you use stone in this way,” says Solis. Both houses also incorporate browns and beiges; plaster walls, including tadelakt in the baths; plenty of wood; and natural fabrics like cotton velvet and linen.

A closer look at these at-first similar homes, however, reveals substantial differences in their details, differences that have everything to do with their distinct historical narratives and the people who inhabit them.

The Point Dume residence— which the Solises share with their children, Lucien and Josephine, and two dogs — is a 1950s colonial that Solis renovated. At first, she was determined to open the interiors up and do away with the warren of smaller rooms. But getting city approvals in Malibu is complex at best, let alone when the administration is backlogged in the aftermath of a pandemic. So, she says, “we decided to capitalize on the smaller rooms and make them incredibly charming. I had a real desire to bring romance to the spaces.”

To elevate the architectural envelope, Solis laid French-white-oak floors and switched out the modern door trim for natural wood moldings that, she says, “give rooms more of a nod to their history.” She also added a false vault in the family room and coffers on the dining-room ceiling. For furnishings, she deployed pieces from her Galerie Solis lines: the Classic sofas, Relic coffee table and Royal lounge chairs in the living room, for example, and the Deco-inspired Crowne chair in the library.

She also installed many vintage and antique pieces that recount her personal tale of taste and style. Mid-century Pierre Jeanneret Capitol Complex chairs, for instance, surround the dining table, which sits near a 1940s French sideboard. And the family room features a Madsen Schubell Pragh seat and a Frits Henningsen wingback chair. These items convey the impression of an older house whose contents were collected over time.

Stanley’s new-build house had no such architectural provenance to allude to. But, says Solis, “Ronnie is Tongan and African American. Elements of the design connect with heritage storytelling.” The envelope is composed of plaster walls and polished-concrete floors, given warmth by the extensive use of custom white-oak millwork. “It’s very calm, very neutral,” says the designer, “and more about the feel and texture of fabrics to promote serenity. It’s all about feeling restorative.”

The cultural heritage references take various forms. A collection of vintage clay vessels, for example, lines the kitchen wall. Mostly from Africa — although Solis says there are likely some Chinese pots as well — they project a rustic utility that imparts age and a sense of narrative to interiors that are quite sophisticated. An African mortar for grinding grain, repurposed as a planter, in the great room, and an antique burlwood table from Galerie Solis in the entry, as well as an African stool in the primary bath, serve the same function.

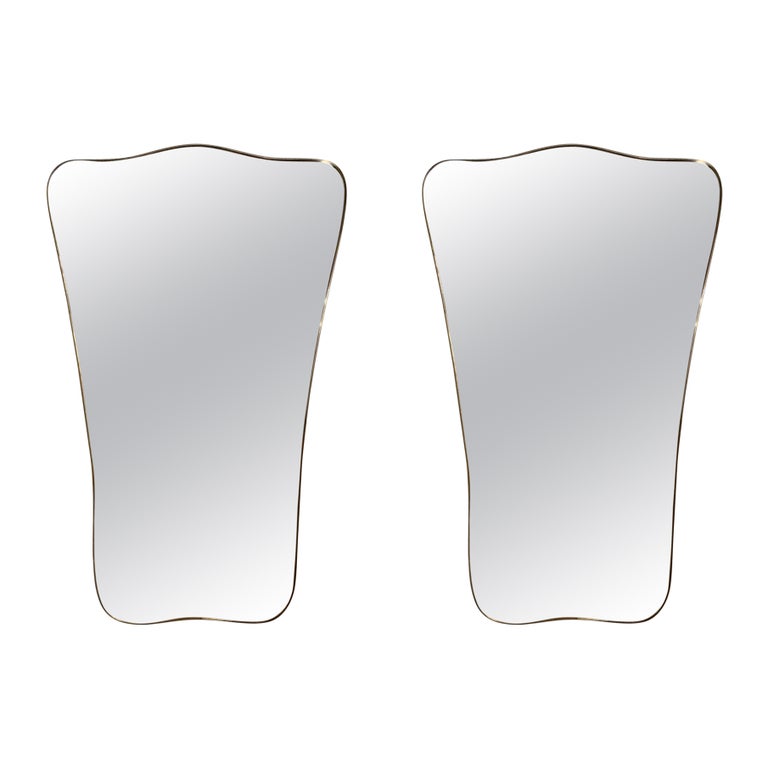

These mingle with vintage finds — not least a set of Mario Bellini’s Cab chairs placed around the dining table — and contemporary pieces, like a Living Divani sectional sofa in the great room. The house’s lighting is particularly interesting and also ranges over eras, from 1960s Italian lamps in a guest room to contemporary fixtures like rewire’s Castanet brass sconces in a powder room and Apparatus wall lights in the primary bedroom.

Both homes embody storytelling through materials, finishes and objects, even as the palettes and Solis’s stylistic signatures remain consistent. And they do so in a way that is oblique rather than obvious, lyrical rather than literal. “It’s about admiring the patina of life,” says Solis.